Trouble in a History Class

(Someone fired a shot!)

Screen 1 of 3

The study of history--or any other subject--can be either exciting or dull,

depending on the teacher. At least, this seems to be true at the high school

level. Graduate students are usually able and motivated enough to be successful

in advanced study, with but little guidance from their professors. And alert

undergraduates who wish to learn can generally progress satisfactorily in regular

college classes.

(Someone fired a shot!)

Screen 1 of 3

But high school students are far more dependent upon the teachers in whose classes they find themselves. If the high school teacher is well grounded in the subject being taught, as well as being enthusiastic and knowledgeable about how adolescent boys and girls learn most effectively, then the teaching-learning process at this level is usually successful. When these conditions do not exist, however, sound learning is not likely to take place.

During my four years as a student at Bowling Green High School, I was fortunate to have many excellent teachers. But I also had some others who were not at all effective. The teacher in this latter group I remember most vividly was a Mr. Oller, who was assigned to teach several courses in history each year. In the fall of 1925 I was enrolled in a sophomore class in American history taught by this man.

I was but fourteen years old at the time--hardly mature enough to be serious about the study of history; and regrettably Mr. Oller was of very little help to any of us in the class, since he neither understood nor liked boys and girls of my age. His negative feeling about teenagers was obvious to everyone around him, and as a result my classmates and I frequently responded with disorderly behavior, which must have irritated and frustrated him even more.

I remember he would quite often stand silently at the window with his back to the class--sometimes for five or ten minutes at a time without moving--apparently oblivious of the talking and general commotion allover the room.

Upon one of these occasions, Howard Smith, a short pudgy student in the class, went up to the teacher's desk close to the window to ask Mr. Oller a question. As Howard began speaking, Mr. Oller whirled around and without any warning picked up the wastebasket and turned it upside down over Howard's head, the papers and trash falling all around them both. Everyone laughed--at that age we seemed always ready to laugh at anything, funny or sad--but not Howard this time. He was stunned in disbelief and said nothing. Neither did Mr. Oller speak. He just calmly turned around and continued his silent staring out the window.

With such conditions prevailing, most of us in the class were usually planning or doing things not at all related to the study of history. Poor Mr. Oller. I felt sorry for him, but still did little to help the situation.

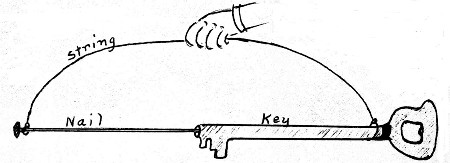

One day I brought to class a gadget I had made at home the night before. It could have been called a firearm, I suppose, since its operation included a sort of explosion. But at best it was a crude contraption, made up of a hollow-core metal key, a nail, and piece of string. (The sketch below will give the reader a rough idea of what it looked like and how it worked.)